Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin 's Suitcase*

DUYGU DEMİR

November 26, 2013

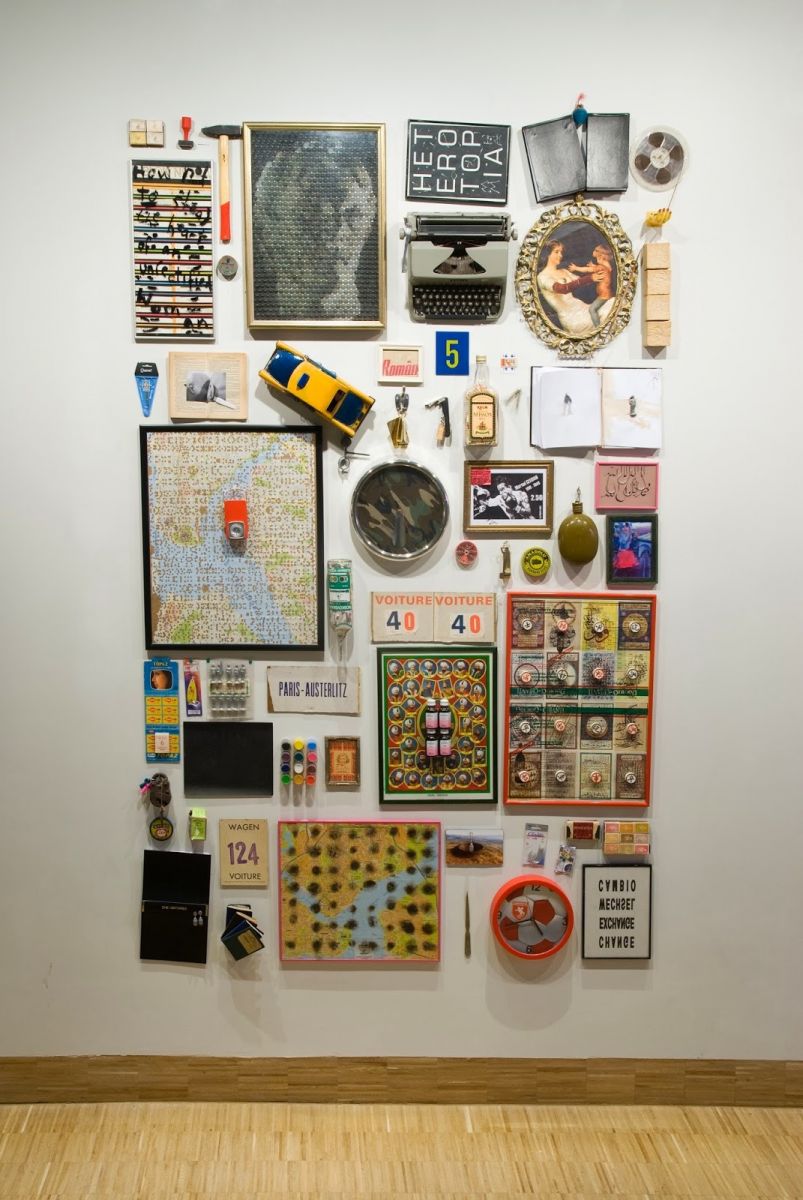

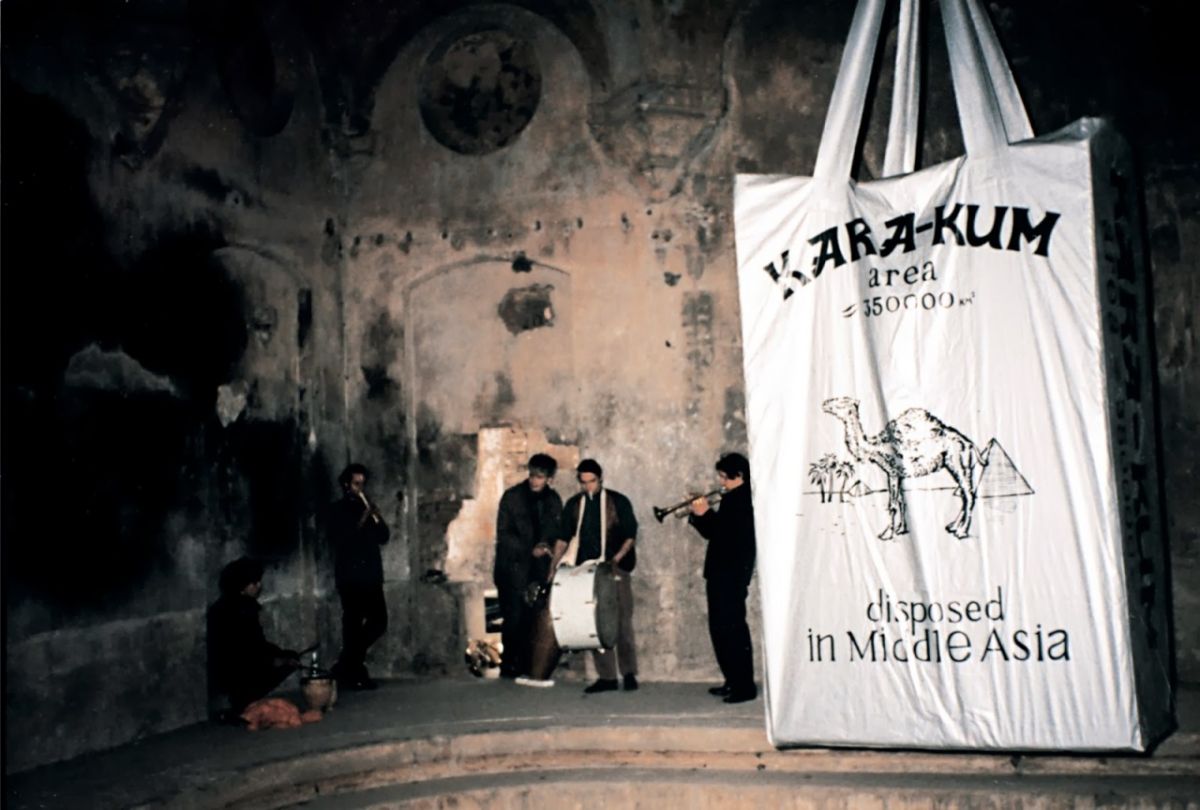

Installation view from Grup Grip-in’s Driftmentary at SALT Galata, 2013

Grup Grip-in, named after the Turkish painkiller available on the market since the 1930s, comprised Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin and a trio of his former students1 —who are now all well-established designers. This year, SALT invited the surviving members to reinterpret the display of Alptekin’s collection of books and ephemera located at SALT Galata. Having taken a course2 in the philosophy of art from Alptekin during their graduate years in the early 1990s and forming the collective with the artist, members of Grup Grip-in are intimately familiar with Alptekin’s preference for collective work rather than for individual authorship, as well as his life-long fascination with kitsch and his refusal to distinguish products of high and low culture. They called their intervention “Driftmentary: Index and Circulation.” Theirs was a simple but telling gesture of listing all the materials collected by Alptekin, on the glass panels in front of his permanently installed library. This ranged from old cameras to the refreshment-towels collected from each and every restaurant and hotel he visited, from key-chains to plastic hands, from puzzles to pocket knives. It was a documentary presentation of a drifter in soul and a collector at heart. The only part of the collection missing from this presentation —because this part of the archive is kept at his home at his family’s request— is perhaps the strongest evidence of Alptekin’s itinerant nature: his collection of more than sixty thermoplastic terrestrial globes.

Starting in the early 1990s, Alptekin focused on an artistic production that explored the effects of globalization, cross-cultural image circulation, immigration and exile. His multi-referential work—consisting of photo-installations, collages, videos, and objects—express a multi-layered visual language. His choice of materials was always informed by the idea of mobility: be it the readymade objects he collected on his travels that found their way into his installations, the newly imported and degenerated technology of commercial lighting and outdoor signage systems that quickly entered and left the urban fabric or photographs taken on unfrequented streets with cameras bought from flea markets. Global junk was Alptekin’s treasure chest. He always chose the road less traveled: whether it was eating on or roaming the streets of the other side of the six-lane Tarlabaşı Avenue in his hometown rather than the glittering pedestrian avenue İstiklal Caddesi or using bunkers in Eastern Europe and Turkish baths in the Balkans for exhibition venues rather than white-walled rooms of Western European museums. Alptekin may have been a drifter, but his destinations of choice were not coincidental; they were reflections of his hyper-awareness of an alternative affluence.

How much can you fit in a suitcase?

Michael Morris and Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin held their first collaborative solo show, which they called Tezgâh/Hierarchy, in Ankara just a year after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The end of the Communist era was the beginning of greater mobility, for people as well as for objects and goods of all kinds. This movement allowed for an unofficial influx of materials into Turkey and the greater region around it, causing an undercurrent of change in the country’s visual culture. The concept of hierarchy referred both to their own way of working, which was a horizontal collaboration, and also to the denial of the distinction between “high” and “low” culture, which both of them embraced. In Turkish, Tezgâh means a stall, a shop counter or a makeshift shop or display-area on the street, marked by a piece of fabric that the goods are displayed on, and it became a key concept in describing their interests at the time. They approached exhibition-making as a kind of “setting-up shop,” a display of goods, a non-hierarchical presentation of “things.”

It wasn’t just the conceptual proximity of an exhibition and the logic of the tezgâh set-up, but also the material quality of the bazaars, the Russian and Romanian markets in Beyazıt, or the stalls in Karaköy that informed their practice. Goods from ex-Communist lives—cheap Vodka and caviar, cigarette packs, razor blades, matches, postcards, stamps and lead soldiers—found their way to these tezgâh in Istanbul, where they were then picked up by Morris and Alptekin, scavengers of these “…endless mythologies.” Alptekin describes their visits to such markets:

“We are befuddled by the hierarchical symmetry among the tezgâh and whatnot on them. The worlds in the infinite space among horizontal strata and vertical layers mercilessly set us up… And between the two of us, there arises the hierarchy of working together, of sharing the work and producing. The only stall with two owners. We both own this tezgâh, and neither of us does.”3

These bazaars and stalls were intertextual libraries for Alptekin and Morris. I imagine them stuffing their findings into their suitcases at the end of their weekend trips, returning from Istanbul to Ankara where they taught4, keeping the empty bottles of vodka they drank the night before, the packs of the Russian cigarettes they smoked, the boxes of the matches they used, the tin containers of caviar they ate at dinner. These items would eventually find their way into their two-dimensional and three-dimensional collages named after that non-place and the place for everything in flux, Foucault’s “heteretopia”; the places that “are absolutely different from all the sites that they reflect and speak about….”5 The Heterotopia collages brought together all kinds of objects and ephemera, allowing for and inspiring multiple associations in various registers, as if they were dream-like mental spaces, where ideas unfolded not in linear time but simultaneously and disorderly, real and absolutely unreal at the same time.

Paper or plastic?

I never had the chance to meet Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin in person, let alone go shopping with him, but I have a strong inclination to believe he would choose “plastic.” His works often speak of “material poverty”6 and plastic is the ultimate signifier of dirt-cheap production, instant circulation and rapid consumption. “Alptekin’s works exist within the realm of exuberant poverty, and their seduction comes only from the uncanny alliances he produces from their unconnectedness.”7

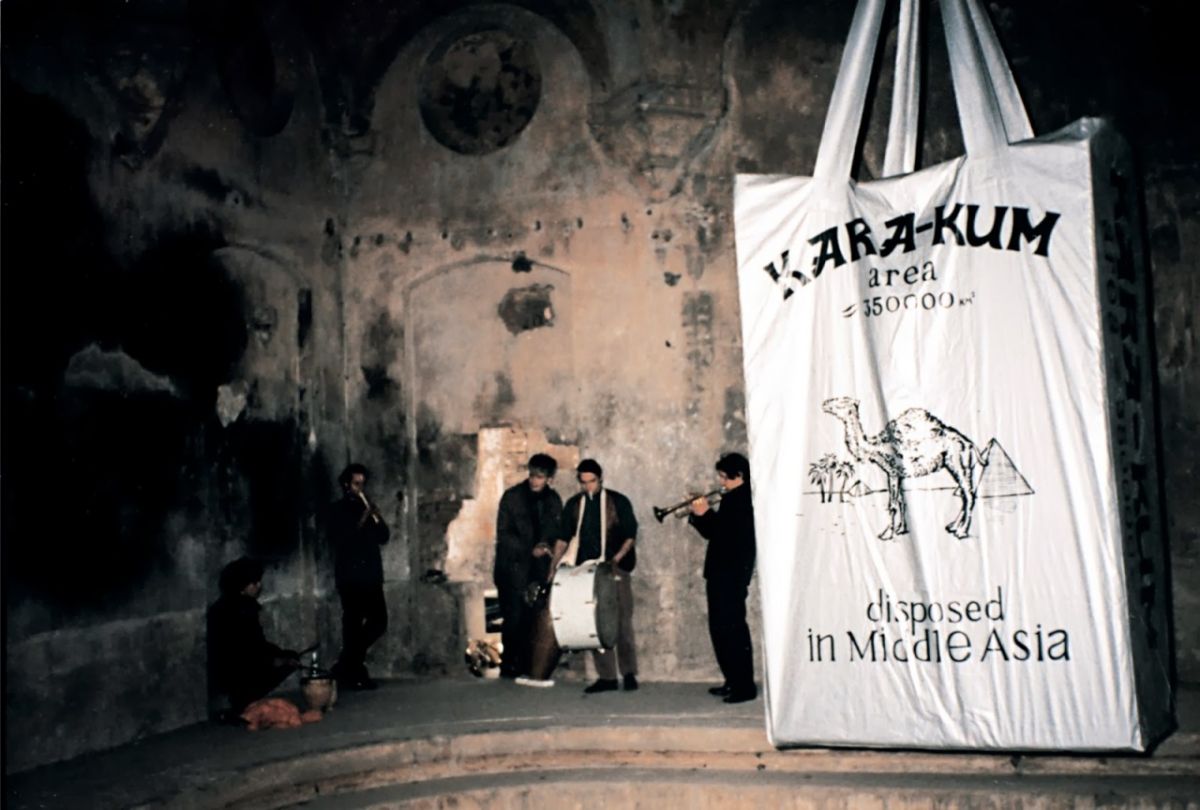

The plastic bag was a semantic tool that bore the traces of a puzzle: it could be used in order to deconstruct the conditions of its existence, and hence was the perfect readymade. In 1995, for their final collaboration, Alptekin and Michael Morris decided to blow-up a plastic bag that they came across during one of their archeological expeditions.8 For them, the bag, which featured the all-too-familiar imagery of the camel with pyramids in the background “borrowed” (but in fact pirated) from Camel cigarette packs, with “Kara-Kum” written at the top, needed no more than the gesture of aggrandizement, like an Oldenburg piece. The object was already rich with third-world implications: the Camel-brand camel, which mistakenly connects Turkish tobacco to desserts and the Egyptian pyramids, the contraband appropriation of the false-imagery by its new brand KARA-KUM (which in Turkish means “Black Sand”), an actual desert in Turkmenistan.

What does it mean that the bag claims some unknown thing is “disposed in Middle Asia” against the background of a fantasy Oriental dwelling? We’ll never know. It was such examples of broken histories and unfinished sentences that Morris and Alptekin were after, visual conundrums that didn’t make direct pronouncements but rather carried traces of other globalisms. For Alptekin, globalization did not mean well-orchestrated worldwide exchanges of national and cultural resources, but unmonitored motion and fortuitous collisions. “The ‘other’ globalism does not operate in linear time; it is truncated, coarse and thuggish.”9

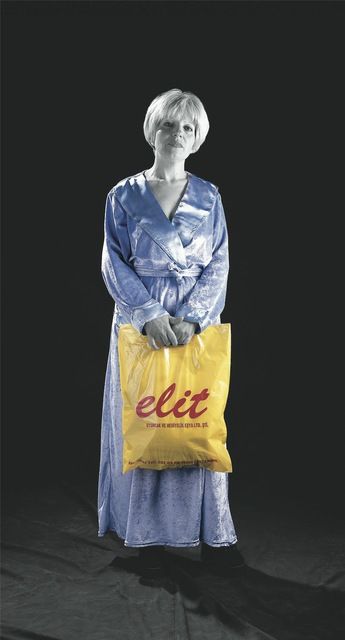

In 1999, Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin showed his works in an exhibition that would be the only solo presentation of his work in Istanbul. The exhibition featured a row of photographs printed on vinyl (another printing technique that made its way to Istanbul’s streets in those days, the latest in technology and the cheapest in cost, immediately and naturally embraced by Alptekin), which included three studio portraits against a black background. One of them featured a pack of cigarettes, by now a signature referent for Alptekin, but it is the other two that treated plastic bags as symbols in the style of classical Western portraiture. One of the portraits featured Vildan, Alptekin’s partner at the time, in a light blue velvet robe, holding a plastic bag that read “Elit.” Vildan was an illegal immigrant in Turkey, who had to succumb to menial work despite her education, embodying the lives of all those economic refugees who are shortchanged, not able to perform their actual occupations, hence becoming embodiments of relational social status. The other figure, the driver of one of Alptekin’s friends, carried a plastic bag printed with the word “dreams.” The plastic bags bearing the words “elite” and “dreams” served as poignant regalia of their social, financial and psychological constrictions. Alptekin’s use of the mannerisms of 19th-century European oil painting portraiture in studio photography, adapted to the conditions of the late 20th century, was perhaps a depiction of the new elite with the available technology: these floating, somewhat misfortunate characters were themselves symbolic figures of the other globalism that Alptekin was so adamantly tracing, “parallel yet distinct from the global capital circuit.”10

Distance: Physical vs. Psychological

One of Alptekin’s favorite novels was Jules Verne’s Kéraban-le-Tetu, or Kéraban the Inflexible (1883). It is the story of a tobacco merchant from Istanbul, who wants to take his agent, visiting from the Netherlands, out for a dinner in Üsküdar, on the Asian side of the city. When they find out that there is an extra tax for crossing the Bosphorus, Kéraban decides that they will travel all around the Black Sea and get to the Asian side via this insensibly long route. In the end, they complete the journey—paying a lot of money along the way—and return to Istanbul on time for a wedding they needed to attend. While Alptekin’s plans to trace this imaginary journey on a boat with other artistic and cultural collaborators was never realized,11 his travels and hence the works informed by them embodied a similar sensibility:

![Suitcase 5 Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin, detail from <i>Sur les Traces de Jules Verne: a Propos de Kéraban</i>, [Tracing Jules Verne], 2000](/directus/media/thumbnails/suitcase_5-png-1200-1200-false.jpg)

“…The notion of distance is very important in Verne’s novel. The hero has no notion of distance. He promised dinner to his guest and they went all around the Black Sea, emphasizing distance as an extremely paradoxical idea. For me, Sofia in Bulgaria is far and Bucharest is very far for some reason, yet going to Switzerland or to London is not far in terms of paper work such as visas, the operation of plane schedules or in terms of linking systems. This is also the same for people who are in constant migration and for whom there are many borders and difficulties through which they move. For them, the same notion of time does not exist. They might take a minibus from İstanbul and be in Moldavia in two or three days. And if somebody is sick they take the person to Siberia for a cure with a quite different conception of distance and time. This is very important in the novel — very important — that nomadism in relationship to time and space is strange and impossible to conceive of when we try to understand its structure. Within the change of locality and the map of the movement, the model of space becomes a fugitive reality between hospitality and hostility. The notion of guest, visitor, outsider, or stranger, changes within and throughout the use of the root-term “hospes” (from the Latin)…”12

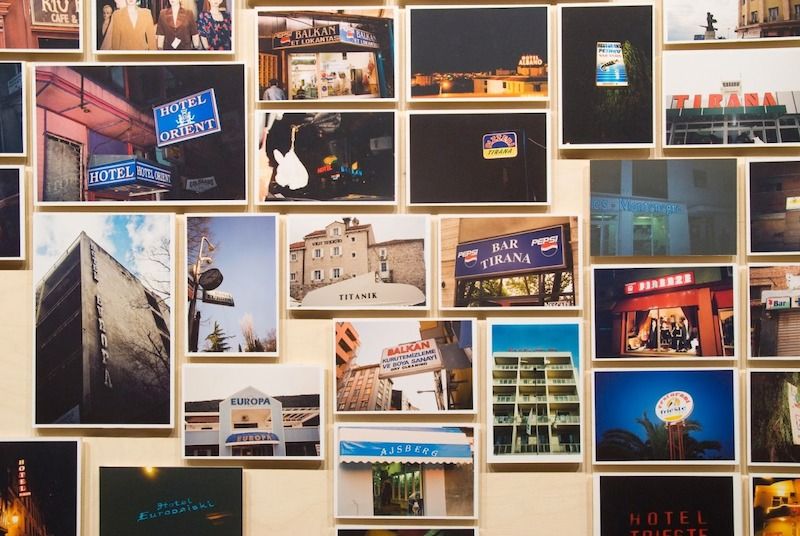

Alptekin’s work H-Fact: Hospitality/Hostility (2003-2007) began as a series of photographs he took of hotel signs, not necessarily on international journeys, but along the less traveled roads of Istanbul, those streets where decrepit hotels bore names of faraway places, of Sarajevo, Berlin, Dallas, Padova and Florida. First shown under the title Capacity, in 1998, the installation consisted of the title word spelled out in red LED neon flex letters that he placed on top of cheaply printed and mounted photographs. The work spoke the language of side streets and alleyways rather than boulevards and main roads, of cities hostile to their own residents and guests. Over time, the work grew with international travels, new and unexpected encounters turned into immense photographic installations, and eventually, to plexi hotel sign installations. These signs, which found Alptekin (as in the case of the Jamaica bar in Bristol or the Cosmos Hotel in Ulan Bator), as much as Alptekin found them, all over the world, not only signify heterogeneity and reaches of mobility but also ideas of nomadism, translocation, longing for a place, and a sense of distance that is more psychological than physical.

Globe-trotting or self-imposed exile?

In 2004, Alptekin wrote an essay entitled “Traveler as artist like lost luggage in the wrong airport” when he was asked to give a talk on the notion of “Artist as Traveler.” In the text, he quotes William Gibson: “Souls can’t move that quickly, are left behind, and must be awaited, upon arrival, like lost luggage.” Did Alptekin have time for his soul to arrive while he was traveling? The image of a dry fish hung around a suspended plastic globe appears in my mind (Geographical Intersection, in collaboration with Michael Morris, 1995). The fish, salted and dried so that it can withstand the effects of time and travel, is a signifier of a jaded, worn-out mobility. It reappears in his installation Winter Depression (1998), lying on the diagnosis table from his doctor-father, inevitably reading as a substitute for the artist himself. This acute attention to those on the move while at home, and the amount of traveling to the destinations Alptekin chose to travel to bring up the question of whether his mobility was a form of self-imposed exile.

“Working while on the run, penetrating the local essence of another culture you are visiting, maybe being a parasite, dislocation and displacement, engaging in production as a voluntary exile may be the romantic side to it. On the other hand, the emotional aspect infused into the works is not about romanticism. It’s a form of melancholy. This is something that is already intrinsic to the things and places I look at, the things I construct and turn into incidents by borrowing them from life.”13

His work Heimat (2001), made out of large sequins and spelling out the words Heimat and toprak (“Heimat” means “homeland” in German; in Turkish, toprak means land, and can also be used to refer to a person that comes from the same place as you) with the colors of the German flag. The way that the sequins glittering faintly in the breeze provided by a fan point to this sense of heightened empathy, of being away from home, of longing, a certain melancholy and fragility. Another work that embodies an even bleaker sense of melancholy is Mattresses to Imaginary Destinations (2003), which comprised of mattresses with blankets on them (the colors and floral design of which invoke the same “material poverty” as in earlier works) that were scattered on the floors of public buildings in Iaşi in Romania, inviting viewers to sit or lie on them. Was Alptekin inviting the viewers to sit down, to wait for the arrival of their souls?

“We are familiar with the notion that the reality of travel is not what we anticipate… If we are inclined to forget how much there is in the world besides that which we anticipate, then works of art are perhaps little to blame, for in them we find the same process of simplification or selection at work as in the imagination. Artistic accounts involve severe abbreviations of what reality will force upon us… Which explains the curious phenomenon whereby valuable elements may be easier to experience in art and in anticipation than in reality. The anticipatory and artistic imaginations omit and compress, they cut away the periods of boredom and direct our attention to critical moments and, without either lying or embellishing, thus lend to life a vividness and a coherence that it may lack in the distracting woolliness of the present… A dominant impulse on encountering beauty is the desire to hold on to it: to possess it and give it weight in our lives. There is an urge to say, ‘I was here, I saw this and it mattered to me.”14

Alptekin saw artistic practice as a way of attaining knowledge: his interest was in objects that themselves took unintended trips and arrived at unforeseeable locations, and along the way took on unanticipated meanings through their dislocation. He made work with materials that traveled easily, utilizing technologies that were quickly adopted. Alptekin’s choice of materials traced these voyages and registered shifts in their meaning as signifiers of capitalist deterritorialization, specifically as they became vectors in peripheral locations, bearers of other globalisms. His life and practice was of being on the road, of observing, and welcoming what he saw into his work. He traveled far, in the way he conceived distance, to psychologically distant lands. His works that were inextricably intertwined with his life produced a new sensibility, a sort of knowledge about nomadic, dislocated, peripheral aspects of globalization. He found the global underbelly in cigarette packs, plastic bags, blankets and hotel signs.

“Travel opens an added and complementary aspect to art as knowledge. An artist deals with another kind of cognitive experience and action. What is happening when we travel: the changes of mood, mode and motion, displacement, decontextualizing things, the self and referring again to the situation. Travel urges artist to develop an act of positioning, a critical view so as to hand back things and ideas. This instant construction of situation/s provides critical knowledge, another knowledge, a different knowledge, but also the same knowledge captured and experienced differently than how we practice it in dealing with life and living. The structure and chemistry of the artist and travel: Travel is an escape from habit and everyday life. The artist is constantly escaping. Travel is a marginal experience; the artist stays in the margin to reach the real universal center.” 15

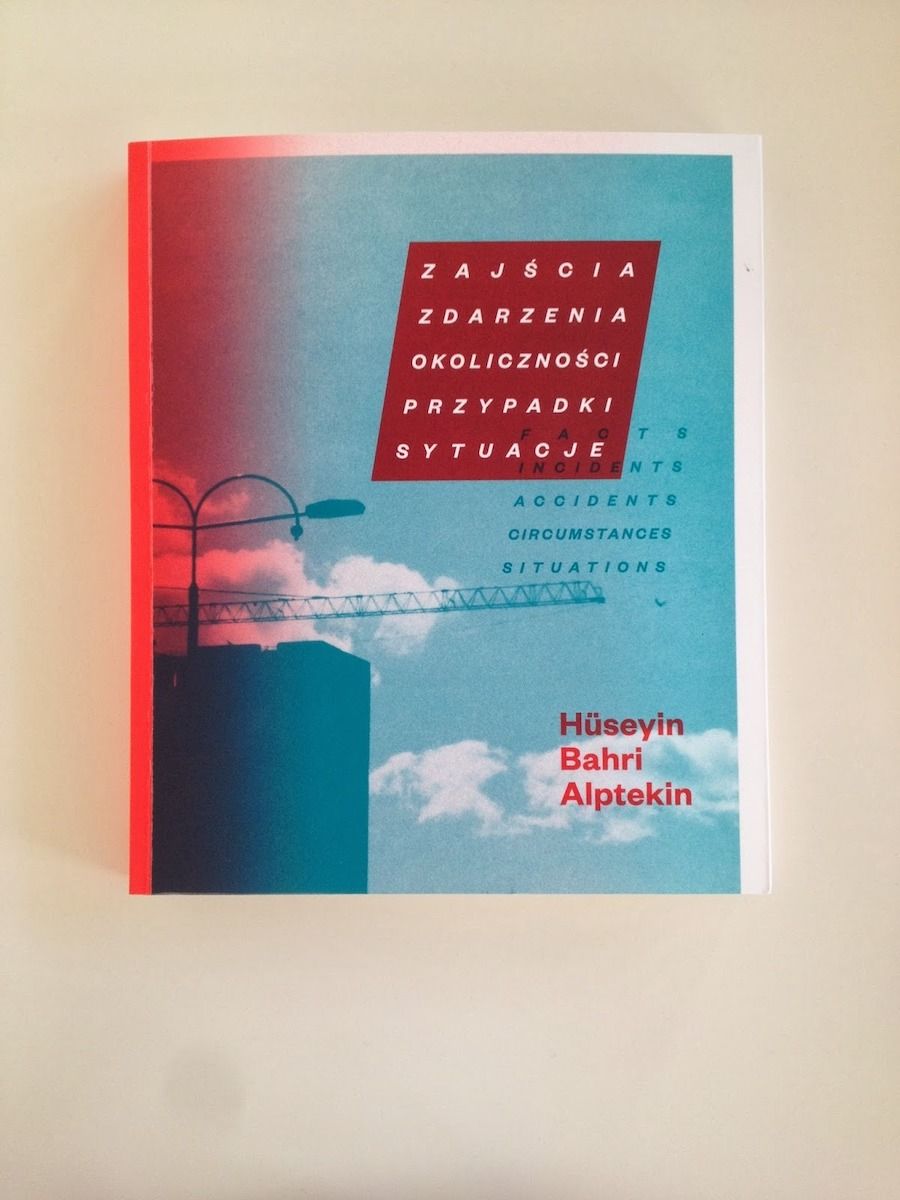

*This text was commissioned by Muzeum Stzuki Lodz for the catalogue of the Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin exhibition entitled Facts - Incidents - Accidents - Circumstances - Situations, curated by Joanna Sokołowska, Magdalena Ziółkowska.

Starting in the early 1990s, Alptekin focused on an artistic production that explored the effects of globalization, cross-cultural image circulation, immigration and exile. His multi-referential work—consisting of photo-installations, collages, videos, and objects—express a multi-layered visual language. His choice of materials was always informed by the idea of mobility: be it the readymade objects he collected on his travels that found their way into his installations, the newly imported and degenerated technology of commercial lighting and outdoor signage systems that quickly entered and left the urban fabric or photographs taken on unfrequented streets with cameras bought from flea markets. Global junk was Alptekin’s treasure chest. He always chose the road less traveled: whether it was eating on or roaming the streets of the other side of the six-lane Tarlabaşı Avenue in his hometown rather than the glittering pedestrian avenue İstiklal Caddesi or using bunkers in Eastern Europe and Turkish baths in the Balkans for exhibition venues rather than white-walled rooms of Western European museums. Alptekin may have been a drifter, but his destinations of choice were not coincidental; they were reflections of his hyper-awareness of an alternative affluence.

How much can you fit in a suitcase?

Michael Morris and Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin held their first collaborative solo show, which they called Tezgâh/Hierarchy, in Ankara just a year after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The end of the Communist era was the beginning of greater mobility, for people as well as for objects and goods of all kinds. This movement allowed for an unofficial influx of materials into Turkey and the greater region around it, causing an undercurrent of change in the country’s visual culture. The concept of hierarchy referred both to their own way of working, which was a horizontal collaboration, and also to the denial of the distinction between “high” and “low” culture, which both of them embraced. In Turkish, Tezgâh means a stall, a shop counter or a makeshift shop or display-area on the street, marked by a piece of fabric that the goods are displayed on, and it became a key concept in describing their interests at the time. They approached exhibition-making as a kind of “setting-up shop,” a display of goods, a non-hierarchical presentation of “things.”

It wasn’t just the conceptual proximity of an exhibition and the logic of the tezgâh set-up, but also the material quality of the bazaars, the Russian and Romanian markets in Beyazıt, or the stalls in Karaköy that informed their practice. Goods from ex-Communist lives—cheap Vodka and caviar, cigarette packs, razor blades, matches, postcards, stamps and lead soldiers—found their way to these tezgâh in Istanbul, where they were then picked up by Morris and Alptekin, scavengers of these “…endless mythologies.” Alptekin describes their visits to such markets:

“We are befuddled by the hierarchical symmetry among the tezgâh and whatnot on them. The worlds in the infinite space among horizontal strata and vertical layers mercilessly set us up… And between the two of us, there arises the hierarchy of working together, of sharing the work and producing. The only stall with two owners. We both own this tezgâh, and neither of us does.”3

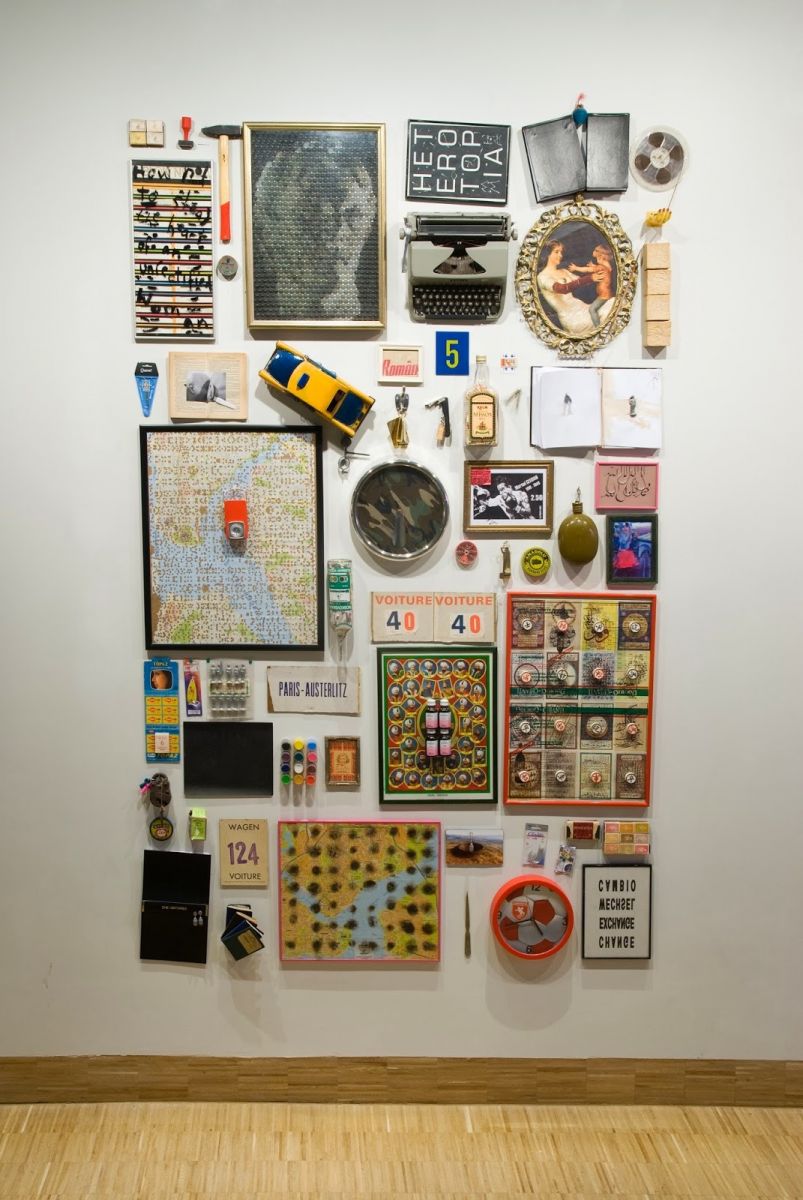

These bazaars and stalls were intertextual libraries for Alptekin and Morris. I imagine them stuffing their findings into their suitcases at the end of their weekend trips, returning from Istanbul to Ankara where they taught4, keeping the empty bottles of vodka they drank the night before, the packs of the Russian cigarettes they smoked, the boxes of the matches they used, the tin containers of caviar they ate at dinner. These items would eventually find their way into their two-dimensional and three-dimensional collages named after that non-place and the place for everything in flux, Foucault’s “heteretopia”; the places that “are absolutely different from all the sites that they reflect and speak about….”5 The Heterotopia collages brought together all kinds of objects and ephemera, allowing for and inspiring multiple associations in various registers, as if they were dream-like mental spaces, where ideas unfolded not in linear time but simultaneously and disorderly, real and absolutely unreal at the same time.

Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin in collaboration with Michael Morris, Heterotopia, installation with found objects, installation view from Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin - I am not a Studio Artist exhibition at SALT Beyoğlu, 2011

Paper or plastic?

I never had the chance to meet Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin in person, let alone go shopping with him, but I have a strong inclination to believe he would choose “plastic.” His works often speak of “material poverty”6 and plastic is the ultimate signifier of dirt-cheap production, instant circulation and rapid consumption. “Alptekin’s works exist within the realm of exuberant poverty, and their seduction comes only from the uncanny alliances he produces from their unconnectedness.”7

The plastic bag was a semantic tool that bore the traces of a puzzle: it could be used in order to deconstruct the conditions of its existence, and hence was the perfect readymade. In 1995, for their final collaboration, Alptekin and Michael Morris decided to blow-up a plastic bag that they came across during one of their archeological expeditions.8 For them, the bag, which featured the all-too-familiar imagery of the camel with pyramids in the background “borrowed” (but in fact pirated) from Camel cigarette packs, with “Kara-Kum” written at the top, needed no more than the gesture of aggrandizement, like an Oldenburg piece. The object was already rich with third-world implications: the Camel-brand camel, which mistakenly connects Turkish tobacco to desserts and the Egyptian pyramids, the contraband appropriation of the false-imagery by its new brand KARA-KUM (which in Turkish means “Black Sand”), an actual desert in Turkmenistan.

Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin in collaboration with Michael Morris, KARA-KUM (1995), Desert in the Bath, Török Fürdö, Budapest, Hungary

What does it mean that the bag claims some unknown thing is “disposed in Middle Asia” against the background of a fantasy Oriental dwelling? We’ll never know. It was such examples of broken histories and unfinished sentences that Morris and Alptekin were after, visual conundrums that didn’t make direct pronouncements but rather carried traces of other globalisms. For Alptekin, globalization did not mean well-orchestrated worldwide exchanges of national and cultural resources, but unmonitored motion and fortuitous collisions. “The ‘other’ globalism does not operate in linear time; it is truncated, coarse and thuggish.”9

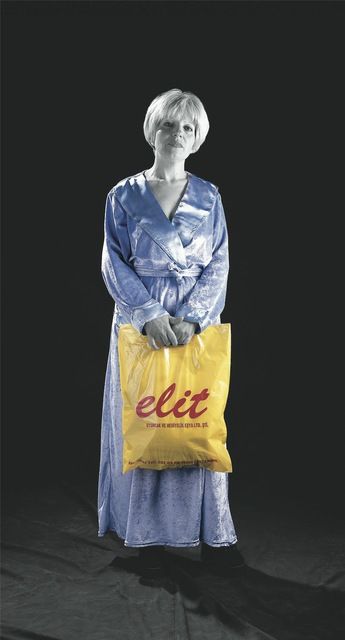

In 1999, Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin showed his works in an exhibition that would be the only solo presentation of his work in Istanbul. The exhibition featured a row of photographs printed on vinyl (another printing technique that made its way to Istanbul’s streets in those days, the latest in technology and the cheapest in cost, immediately and naturally embraced by Alptekin), which included three studio portraits against a black background. One of them featured a pack of cigarettes, by now a signature referent for Alptekin, but it is the other two that treated plastic bags as symbols in the style of classical Western portraiture. One of the portraits featured Vildan, Alptekin’s partner at the time, in a light blue velvet robe, holding a plastic bag that read “Elit.” Vildan was an illegal immigrant in Turkey, who had to succumb to menial work despite her education, embodying the lives of all those economic refugees who are shortchanged, not able to perform their actual occupations, hence becoming embodiments of relational social status. The other figure, the driver of one of Alptekin’s friends, carried a plastic bag printed with the word “dreams.” The plastic bags bearing the words “elite” and “dreams” served as poignant regalia of their social, financial and psychological constrictions. Alptekin’s use of the mannerisms of 19th-century European oil painting portraiture in studio photography, adapted to the conditions of the late 20th century, was perhaps a depiction of the new elite with the available technology: these floating, somewhat misfortunate characters were themselves symbolic figures of the other globalism that Alptekin was so adamantly tracing, “parallel yet distinct from the global capital circuit.”10

Dreams, digital print on vinyl

Elit, (1999), digital print on vinyl

Distance: Physical vs. Psychological

One of Alptekin’s favorite novels was Jules Verne’s Kéraban-le-Tetu, or Kéraban the Inflexible (1883). It is the story of a tobacco merchant from Istanbul, who wants to take his agent, visiting from the Netherlands, out for a dinner in Üsküdar, on the Asian side of the city. When they find out that there is an extra tax for crossing the Bosphorus, Kéraban decides that they will travel all around the Black Sea and get to the Asian side via this insensibly long route. In the end, they complete the journey—paying a lot of money along the way—and return to Istanbul on time for a wedding they needed to attend. While Alptekin’s plans to trace this imaginary journey on a boat with other artistic and cultural collaborators was never realized,11 his travels and hence the works informed by them embodied a similar sensibility:

![Suitcase 5 Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin, detail from <i>Sur les Traces de Jules Verne: a Propos de Kéraban</i>, [Tracing Jules Verne], 2000](/directus/media/thumbnails/suitcase_5-png-1200-1200-false.jpg)

Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin, detail from Sur les Traces de Jules Verne: a Propos de Kéraban, [Tracing Jules Verne], 2000

“…The notion of distance is very important in Verne’s novel. The hero has no notion of distance. He promised dinner to his guest and they went all around the Black Sea, emphasizing distance as an extremely paradoxical idea. For me, Sofia in Bulgaria is far and Bucharest is very far for some reason, yet going to Switzerland or to London is not far in terms of paper work such as visas, the operation of plane schedules or in terms of linking systems. This is also the same for people who are in constant migration and for whom there are many borders and difficulties through which they move. For them, the same notion of time does not exist. They might take a minibus from İstanbul and be in Moldavia in two or three days. And if somebody is sick they take the person to Siberia for a cure with a quite different conception of distance and time. This is very important in the novel — very important — that nomadism in relationship to time and space is strange and impossible to conceive of when we try to understand its structure. Within the change of locality and the map of the movement, the model of space becomes a fugitive reality between hospitality and hostility. The notion of guest, visitor, outsider, or stranger, changes within and throughout the use of the root-term “hospes” (from the Latin)…”12

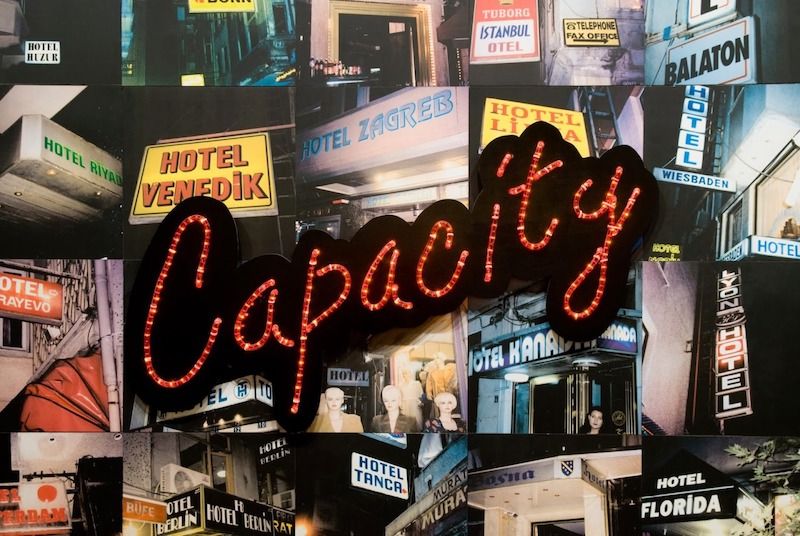

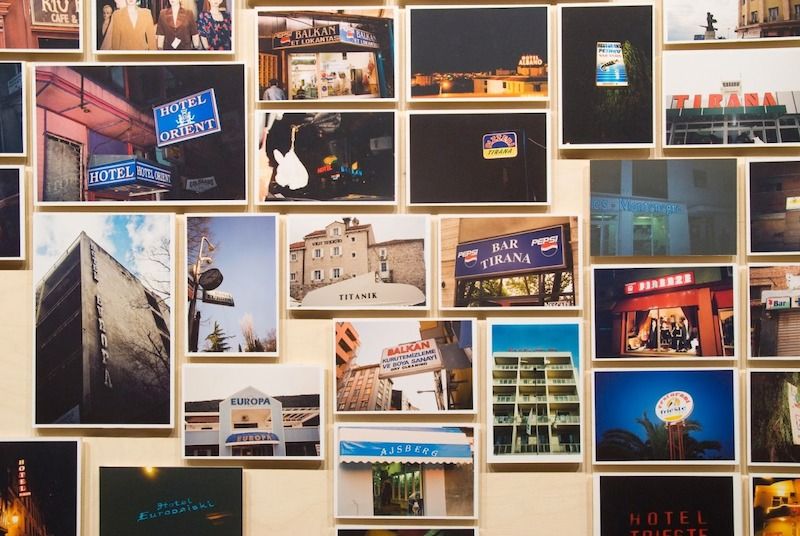

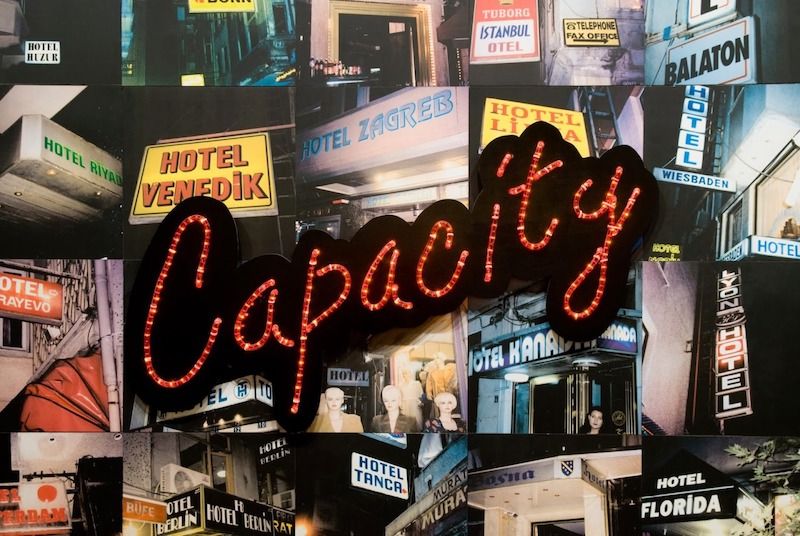

Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin, detail from Capacity (2003, photo- installation)

Alptekin’s work H-Fact: Hospitality/Hostility (2003-2007) began as a series of photographs he took of hotel signs, not necessarily on international journeys, but along the less traveled roads of Istanbul, those streets where decrepit hotels bore names of faraway places, of Sarajevo, Berlin, Dallas, Padova and Florida. First shown under the title Capacity, in 1998, the installation consisted of the title word spelled out in red LED neon flex letters that he placed on top of cheaply printed and mounted photographs. The work spoke the language of side streets and alleyways rather than boulevards and main roads, of cities hostile to their own residents and guests. Over time, the work grew with international travels, new and unexpected encounters turned into immense photographic installations, and eventually, to plexi hotel sign installations. These signs, which found Alptekin (as in the case of the Jamaica bar in Bristol or the Cosmos Hotel in Ulan Bator), as much as Alptekin found them, all over the world, not only signify heterogeneity and reaches of mobility but also ideas of nomadism, translocation, longing for a place, and a sense of distance that is more psychological than physical.

Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin, detail from Capacity/Capacities (1998), digital print on forex, cold neon, regulator

Globe-trotting or self-imposed exile?

In 2004, Alptekin wrote an essay entitled “Traveler as artist like lost luggage in the wrong airport” when he was asked to give a talk on the notion of “Artist as Traveler.” In the text, he quotes William Gibson: “Souls can’t move that quickly, are left behind, and must be awaited, upon arrival, like lost luggage.” Did Alptekin have time for his soul to arrive while he was traveling? The image of a dry fish hung around a suspended plastic globe appears in my mind (Geographical Intersection, in collaboration with Michael Morris, 1995). The fish, salted and dried so that it can withstand the effects of time and travel, is a signifier of a jaded, worn-out mobility. It reappears in his installation Winter Depression (1998), lying on the diagnosis table from his doctor-father, inevitably reading as a substitute for the artist himself. This acute attention to those on the move while at home, and the amount of traveling to the destinations Alptekin chose to travel to bring up the question of whether his mobility was a form of self-imposed exile.

“Working while on the run, penetrating the local essence of another culture you are visiting, maybe being a parasite, dislocation and displacement, engaging in production as a voluntary exile may be the romantic side to it. On the other hand, the emotional aspect infused into the works is not about romanticism. It’s a form of melancholy. This is something that is already intrinsic to the things and places I look at, the things I construct and turn into incidents by borrowing them from life.”13

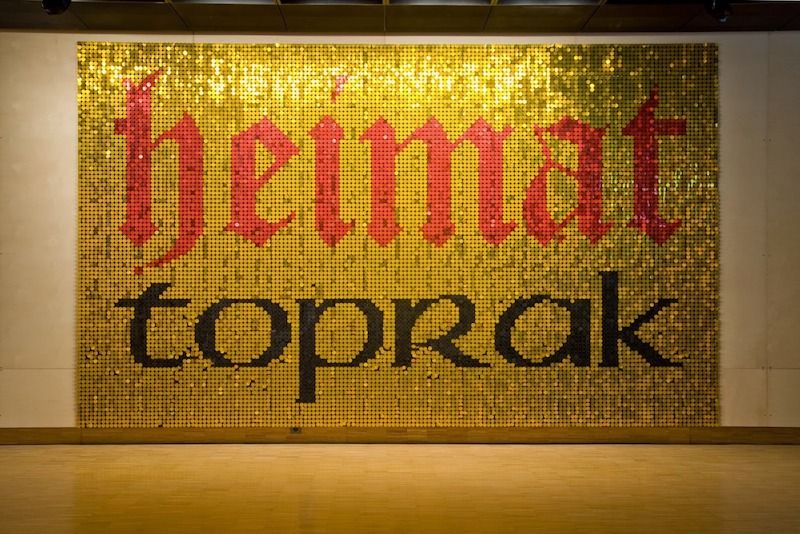

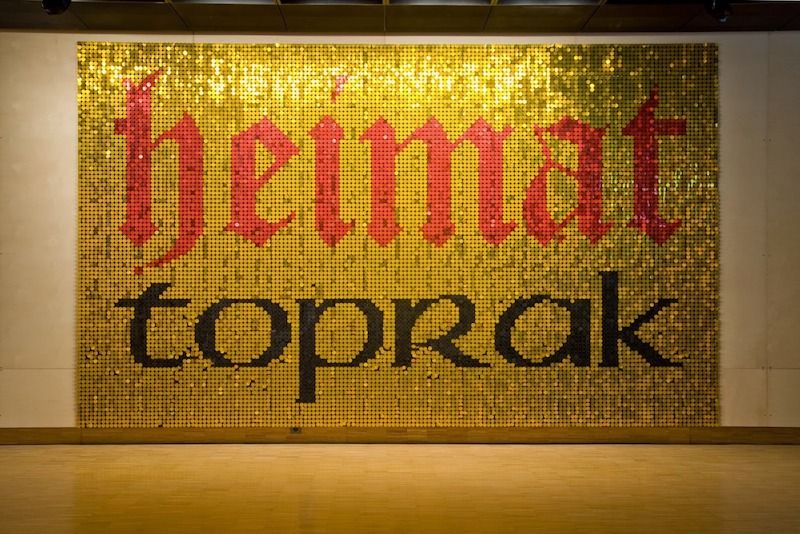

His work Heimat (2001), made out of large sequins and spelling out the words Heimat and toprak (“Heimat” means “homeland” in German; in Turkish, toprak means land, and can also be used to refer to a person that comes from the same place as you) with the colors of the German flag. The way that the sequins glittering faintly in the breeze provided by a fan point to this sense of heightened empathy, of being away from home, of longing, a certain melancholy and fragility. Another work that embodies an even bleaker sense of melancholy is Mattresses to Imaginary Destinations (2003), which comprised of mattresses with blankets on them (the colors and floral design of which invoke the same “material poverty” as in earlier works) that were scattered on the floors of public buildings in Iaşi in Romania, inviting viewers to sit or lie on them. Was Alptekin inviting the viewers to sit down, to wait for the arrival of their souls?

Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin, Heimat toprak (2001), sequins mounted on plastic plates, 3.25 x 4.75m, installation view from Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin - I am not a Studio Artist exhibition at SALT Beyoğlu, 2011

“We are familiar with the notion that the reality of travel is not what we anticipate… If we are inclined to forget how much there is in the world besides that which we anticipate, then works of art are perhaps little to blame, for in them we find the same process of simplification or selection at work as in the imagination. Artistic accounts involve severe abbreviations of what reality will force upon us… Which explains the curious phenomenon whereby valuable elements may be easier to experience in art and in anticipation than in reality. The anticipatory and artistic imaginations omit and compress, they cut away the periods of boredom and direct our attention to critical moments and, without either lying or embellishing, thus lend to life a vividness and a coherence that it may lack in the distracting woolliness of the present… A dominant impulse on encountering beauty is the desire to hold on to it: to possess it and give it weight in our lives. There is an urge to say, ‘I was here, I saw this and it mattered to me.”14

Alptekin saw artistic practice as a way of attaining knowledge: his interest was in objects that themselves took unintended trips and arrived at unforeseeable locations, and along the way took on unanticipated meanings through their dislocation. He made work with materials that traveled easily, utilizing technologies that were quickly adopted. Alptekin’s choice of materials traced these voyages and registered shifts in their meaning as signifiers of capitalist deterritorialization, specifically as they became vectors in peripheral locations, bearers of other globalisms. His life and practice was of being on the road, of observing, and welcoming what he saw into his work. He traveled far, in the way he conceived distance, to psychologically distant lands. His works that were inextricably intertwined with his life produced a new sensibility, a sort of knowledge about nomadic, dislocated, peripheral aspects of globalization. He found the global underbelly in cigarette packs, plastic bags, blankets and hotel signs.

Installation view from Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin - I am not a Studio Artist exhibition at SALT Beyoğlu, 2011

“Travel opens an added and complementary aspect to art as knowledge. An artist deals with another kind of cognitive experience and action. What is happening when we travel: the changes of mood, mode and motion, displacement, decontextualizing things, the self and referring again to the situation. Travel urges artist to develop an act of positioning, a critical view so as to hand back things and ideas. This instant construction of situation/s provides critical knowledge, another knowledge, a different knowledge, but also the same knowledge captured and experienced differently than how we practice it in dealing with life and living. The structure and chemistry of the artist and travel: Travel is an escape from habit and everyday life. The artist is constantly escaping. Travel is a marginal experience; the artist stays in the margin to reach the real universal center.” 15

Cover of catalogue published by Muzeum Stzuki Lodz

*This text was commissioned by Muzeum Stzuki Lodz for the catalogue of the Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin exhibition entitled Facts - Incidents - Accidents - Circumstances - Situations, curated by Joanna Sokołowska, Magdalena Ziółkowska.

- 1.The students were Ali Cindoruk, Eray Makal, Erhan Muratoğlu

- 2.Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin and Vasıf Kortun co-taught a graduate level class entitled "Philosophy of Modern Art" at the Department of Architecture, Fine Arts and Design at Bilkent University in Ankara during the 1990-1991 academic term which analyzed the 1991 exhibition "High&Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture" that took place at MoMA. Grup Grip-in organized an exhibition titled "Popular Myths and Graphic Intertextuality" at ANFA Altın Park in Ankara in 1992, which conceptualized their findings and discussions from this class.

- 3.The Right to a Tezgâh, Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin and Michael Morris, text from Alptekin's archive, printed in I am not a studio artist, published by SALT, Istanbul, in 2011, p.44.

- 4.Michael Morris and Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin were faculty members at the Department of Architecture, Fine Arts and Design at Bilkent University in Ankara in the early 1990s.

- 5.Michel Foucault, Of Other Spaces, Heterotopias, lecture notes published as "Des Espaces Autres" by the French journal Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité in 1984.

- 6.I am borrowing this term from Vasıf Kortun, from the catalogue text for Alptekin's only solo exhibition at Dulcinea Gallery in Istanbul in 1999: Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin-Viva Vaia, reprinted in I am not a studio artist, published by SALT in 2011, p.119.

- 7.Ibid.

- 8.For Morris and Alptekin, trips to shops, markets, bazaars and street stalls were the material source for most of their collaborations.

- 9.Vasıf Kortun in Kriz Viva Vaia, catalogue text, I am not a studio artist, 122.

- 10.Ibid., p.119

- 11.Inspired by Jules Verne's novel, Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin initiated the "Sea Elephant Travel Agency" with a group of fellow artists and art professionals, most of whom were already participants in his LOFT project. The first endeavor of the Sea Elephant Travel Agency was the Black Sea Project. Following the travels of Jules Verne's stubborn tobacco merchant Kéraban around the coast of the Black Sea, Alptekin intended to gather artists, curators, musicians, architects, historians and scientists to board a boat leaving from İstanbul, following the route of Kéraban and anchoring back in İstanbul again after making a full circle around the Black Sea, stopping at ports of Varna, Constanta, Odessa, Sevastopol, Yalta, Rostov, Novossibirsk, Sochi, Batumi, Trabzon and Sinop. "A laboratory of art, science, music and architecture," Alptekin expected the boat to become a site of exchange and production, and planned for artistic interventions, events, panels and performances that would stimulate conversations at each port where the boat anchored. Alptekin envisioned the project and thus the boat-lab "(to) first and foremost operate as a sign of solidarity among the unions by artists and artistic projects and the boat will be vessel for the embodiment of this solidarity." For Alptekin there were two consequential aims of the project; first, the presenting the research undertaken via photographic and video documentation, and secondly, extending the spirit of Kéraban into other regions such as the Baltic Sea and the Barents Sea. It was planned for the boat to take off in August 2003, and sail for two months. Unfortunately, the project was never realized.

- 12.Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin, Mutual Realities, Re-mapping Destinies, 2002

- 13.Alptekin, from an interview with Vasıf Kortun, conducted for the brochure for the pavilion of Turkey, 52nd Venice Biennale, 2007

- 14.Alain de Botton, The Art of Travel, quoted by Alptekin in his text for his artist talk titled "Traveler as artist like lost luggage in the wrong airport" given in Cork, during his residency in Kellerberrin, Australia in 2004

- 15.Alptekin, from the text for his artist talk titled "Traveler as artist like lost luggage in the wrong airport" given in Cork, during his residency in Kellerberrin, Australia in 2004.